Charles Darwin once said that he thought the evidence from the comparative anatomy of embryos was “by far the strongest single class of facts” in favor of common descent (Darwin, 1860) and while it has since been eclipsed by genetics, it remains one of most compelling subsets of evidence for evolution. And perhaps the single most striking detail in the comparative embryology of vertebrates, are the structures colloquially known as “gill slits”.

Embryonic “gill slits” or “branchial clefts” (branchia is Greek for gill) or more properly pharyngeal clefts (grooves, folds, etc.) are part of what is called the “pharyngeal apparatus” found in front (ventral) and sides (lateral) of the head/neck region of all vertebrates in the “pharyngula stage” of development. In “fish”, and the larva of amphibians, these develop into respiratory organs used to extract oxygen from water while in amniotes (“reptiles”, birds and mammals) they are modified into other structures.

Before I go on, a brief digression about “fish”. Throughout this article I will often use “fish” in the generic sense; but it should be noted that the term as it is commonly used—to refer to any vertebrate that swims in the water, has fins and gills—is not a valid scientific classification. This is because the three main types of animals commonly called “fish” —the Chondrichthyes (sharks, rays, skates and chimaeras), the Actinopterygii (ray fined fish, which constitutes the majority of living fishes), and the Sarcopterygii (lobe fined fish, the group from which four legged land animals, i.e. tetrapods, evolved)—are not a monophyletic group. That is they are not very closely related to each other despite some of their outward similarities (like gills). For example the living Sarcopterygii, lung fish and coelacanths share a more recent common ancestor with us (and all tetrapods) than with the other “fishes”.

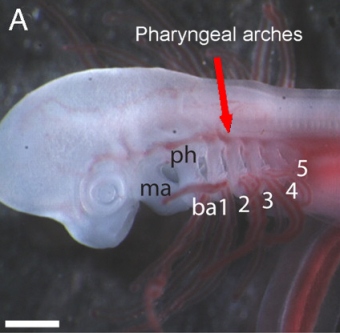

OK, so the “pharyngeal apparatus” consists of a series of paired pharyngeal arches and fissures which develop on the exterior with a corresponding set of pharyngeal pouches on the inside of the throat, separated from the external fissures by a thin membrane (more on the details in a moment). And in fact the possession of these structures at some point in development, along with a hollow dorsal nerve cord, a notochord and a post anal tail, are the defining characteristics of the phylum chordata to which we and all other vertebrates belong.

Please note that the above illustration is diagrammatic and not intended to be photographically accurate (I have to say that lest I be accused by creationists of conveying a fraud). Below are actual photographs of both a skate embryo and a human embryo for comparison. Also note: the gill structures in the embryos of Elasmobranch fishes—the subdivision of Chondrichthyes which contains sharks, rays and skates—are much less derived than in other “fishes” and therefore generally more similar to those of amniote embryos than the corresponding structures in the bony “fishes” (which are significantly modified).

The first of the arches, the mandibular arch, forms the jaw in all jawed vertebrates (Gnathostomes). Most vertebrates develop a total of six arches but the full complement is usually only retained into adulthood by hexanchiform sharks. Hexanchiformes are very plesiomorphic which means that they are more like earlier types of sharks. Some species of hexanchiformes even develop a seventh arch. Likewise the extant jaw-less vertebrate, the lamprey, also have seven gill openings.